Back in the late 60’s and 70’s, fourths were the hippest thing since sliced bread. Jazz entered the age of treble-heavy bass and electric fusion, and musicians were overlaying fresh-sounding (at the time) intervallic fourth patterns over all sorts of funky modal groove tunes.

Back in the late 60’s and 70’s, fourths were the hippest thing since sliced bread. Jazz entered the age of treble-heavy bass and electric fusion, and musicians were overlaying fresh-sounding (at the time) intervallic fourth patterns over all sorts of funky modal groove tunes.

But fourths are so much more than just a few licks to plug in. Let’s explore the harmonic and intervallic possibilities the fourth creates. I hope to open your mind, your practice routine, and your playing. After all, it’s called a perfect fourth for a reason!

Let’s start from the beginning and work our way up.

What is a fourth?

Let’s take 10 seconds and cover the extreme basics. The fourth is an interval. In the key of C, moving from C to F is moving from 1 to 4 if you number each note sequentially:

Harmonically speaking, the fourth takes a similar form. In the key of C, an “F” chord is known as the fourth.

Building a Major Scale Out of 4ths

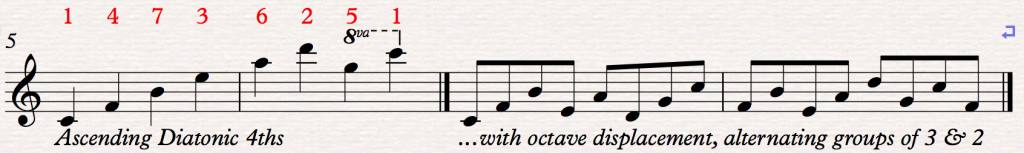

Still staying in the key of C, let’s go back to diatonic intervals. The C-major scale can be spelled out in ascending diatonic fourths, as depicted below, without repeating a note (until you get back to C). Doing so reveals that our harmonic best friends, the ii-V-I (2-5-1) as well as the 3-6-2-5-1, are all constructed using sequential diatonic fourths (note the last 5 numbers in red):

Now, instead of starting from C, start from B: B-E-A-D-G-C-F. What do you get?

All the notes of the major scale constructed purely from sequential perfect fourths

(by starting from B, you avoid going from F to B, which is a tritone rather than perfect fourth). As an aside, you can take this simple concept, alternate 3-2 groupings and octave displacement, and you get a nice little pattern that’s fun to work through in all 12 keys.

Applying it Over ii-V7-I’s

Now that you’re armed with this knowledge, you can start thinking of ways to apply it to your playing. Instead of thinking of 4ths as angular “out stuff” you can throw into modal playing for color, you can string together 7 perfect fourths in a row while staying within a single major key. This opens up some nifty ii-V7-I opportunities:

Not exactly breathtaking, but the octave displacement breaks up the ascending monotony, and it ends with a satisfying piece of voice leading from F to C. Regardless, it’s the foundation of a concept you can begin to explore. Try experimenting by backtracking further along the circle of 4ths, starting “out” and then moving “in” as you move through your line (i.e. add 3 notes before the line: G# – C# – F#).

I was checking out John Swana’s playing over his 4th’s based contrafact “Giants” of Giant Steps on his 2004 release New York-Philly Junction, where he extended the logic above. He’s spicing it up by going down a minor third instead of up a fourth. Actually, the pattern is: A -up 4th – up 4th – shift whole thing up a perfect 5th to E, etc. It’s a very flexible shape.

Chromatic Ascention

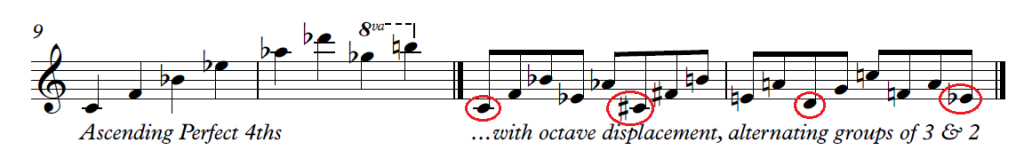

Going a step further, a lot of musicians are still using the more modal perfect 4ths concept that were pioneered 40-50 years ago, but they are continuing to find interesting and robust applications for these shapes. Let’s start by making sure we’re all on the same page: instead of going up a diatonic scale in 4th intervals, you can throw away key and think purely of the perfect 4th interval:

The first 2 measures above illustrate the basic concept. The second 2 measures with the red circles take this basic idea, apply some octave displacement and alternating groups of 3 & 2, and produce yet another interesting pattern. Notice that by grouping the circle of 4ths in sets of 5, you end up ascending in half steps (C – C# – D – Eb) – the circled notes. You can utilize this discovery by applying this concept to any harmonic context with chromatic ascending roots.

Mark Tuner Top Pedal

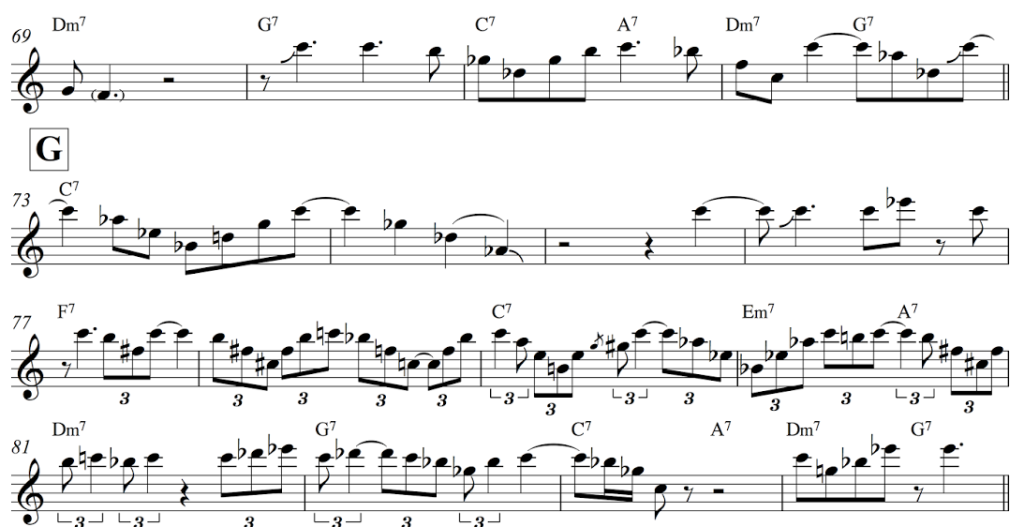

Here’s yet another application. I came across a Mark Turner & James Moody transcription on Kevin Sun’s blog over a blues tune off some obscure Warner Jams record. Moody starts with some very hip stuff (including lots of 4ths!) that you should definitely check out. In listening to Mark’s solo, I recognized a concept he exhaustively explores in his solo playing. He pedals the top note of his line while moving the notes underneath. In this case he kept returning to a C (the root), and underneath he plays descending groups of fourths moving around chromatically. Very interesting use of the shape and great way to apply harmony and create tension. Check it out around the 2:20 mark:

Thanks to Kevin for the great transcription!

Aaron Goldberg Superimposing 4ths, then Resolving

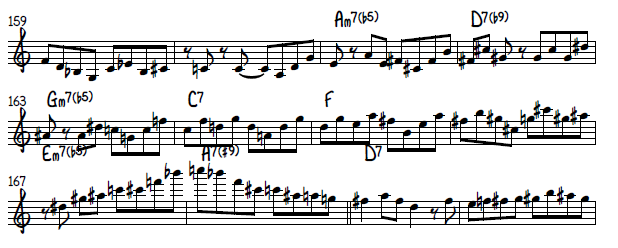

And finally, I return to a solo by Aaron Goldberg I previously featured in my transcription post. It’s over a contrafact of One Finger Snap called Head Trip. In addition to being a great solo, Aaron makes great use of 4th’s throughout in a very integrated and natural manner. Take this snippet that occurs midway through his solo.

(it just so happens that this again occurs around the 2:20 mark):

Here’s the full transcription.

In Conclusion

I hope this opens you up to just a few of the possibilities that 4ths offer. As a warning, don’t overuse them, or you run the risk of sounding formulaic. However, properly applied, 4ths are fun to explore and should be an asset in your improvisational toolbox.