![]() It’s been a whirlwind of a summer. I almost moved to London, but then I heard the burritos over there are terrible, so last week my girlfriend and I moved into a new apartment together instead. So, the posts stopped for a while, but it’s time to get back on the horse!

It’s been a whirlwind of a summer. I almost moved to London, but then I heard the burritos over there are terrible, so last week my girlfriend and I moved into a new apartment together instead. So, the posts stopped for a while, but it’s time to get back on the horse!![]()

I’ve been thinking a lot about harmony and come to believe that the difference between today’s best jazz musicians and the rest of us is their masterful command over the minutia of harmony.

I realized that I don’t have as a good a grasp of the plethora of dominant alterations out there as I should.

Why Harmonic Mastery is ESSENTIAL

Those of you with some degree of jazz exposure may be thinking…

…I know what a dominant chord is, and I know what a b9 and #9 sound like. It’s not rocket science.

Fine. But are you sure you aren’t just blindly applying alterations regardless of each particular context? Do you REALLY know when the piano player is hitting a #11 or b13, or are you just thinking…

…Ah, some sort of altered dominant, time to plug in my angular diminished licks!!

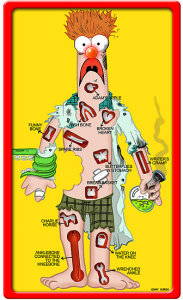

Have you ever played the board game Operation? The basic objective is to use little tweezers to take out tiny plastic organs from a dude’s body without without touching the sides. Jazz harmony functions in a surprisingly similar manner. Your hands don’t have to be perfectly steady and studied to come close to getting it right. But every now and then your hands (ears) aren’t studied enough to make it out (of the harmony) cleanly. The inappropriately dissonant buzzer goes off, Beaker’s nose glows bright red, and you’re busted.

I’m not here to sound the hater-buzzer every time you sit on an F over a C7#11. But I hope to help you understand that the more you play “close enough” with harmony, the further you will be from sincerely obtaining your musical goals.

Non-Dominants

Some chords are pretty straightforward. Major, minor, and half-diminished chords have consistent functions in conventional harmony, and their varieties are limited.

Take the varieties of C major for example. You can play a C major scale over Cmaj7, C6, C6/9; raise the fourth (lydian) and you’ve got the rest of the C major family covered (Cmaj7#11, etc). It’s a good bet that the C major you are playing functions as either the tonic (root), IV, or III (relative major) of the tune.

Similarly, 99% of minor chords you come across are the tonic, iv (relative minor), or ii of a ii-V-I. Again, I’m talking about traditional jazz/western harmony here, not the more contemporary harmonic approach to non-functional chord progressions.

What Makes Dominants So Special

Compared to major & minor, the dominant chord is unpredictable. It’s most versatile yet subtle harmonic family in music.

Before diving into the many forms of the dominant that I cover later, let’s pause to think about WHY it’s so flexible. Go sit down at your piano, play any simple dominant chord (i.e. C-E-G-F), and resolve it to the closest inversion of ANY major or minor chord. It works! I won’t get into why, but the presence of that embedded diminished triad (3-5-b7) creates a lot of tension, and that tension can resolve anywhere, which means that in jazz harmony, the dominant chord can function in many ways.

Western Classical: V7

Classical composers, or really any composer before the early 20th century, would employ the dominant chord in an extremely predictable manner: as a five chord. No alterations were used, and the presence of that embedded diminished triad created all the tension necessary to make the resolution sound good to your ears.

The traditional functions are:

- V7: Resolving to major [V or V7 – I]: The most popular resolution in all of western music.

- V7: Resolving to minor [V or V7 – i]: Note how the dominant structure in classical is maintained between major and minor, meaning that the same set of notes can resolve to either major or minor harmonies.

- I7-IV: Secondary dominants [I7 – IV]: When moving between tonal centers, classical composers often use the dominant of the resolution key (V7 of IV) to prepare the listener for the harmonic transition.

Jazz: Dominants in 2-5-1’s

In jazz, the idea of the secondary dominant is expanded to allow composers to move resolve within and move between tonal centers of a tune, most typically in the form of the ii-V7-I cadence.

The two main varieties of dominants used in 2-5’s are major and minor:

- V7(*): Resolving to major |ii-V7-I|: The ii-V7-I is the foundation of jazz. However, it’s so common that musicians over the years have been spicing it up quite a bit. You’ll find many different forms of the V7 chord (b9, #9, etc.) and you often need your ears to tell you which alteration is being used by the soloist or (as a soloist) rhythm section. More on this in my next post.

- V7(b9): Resolving to minor |ii7b5 – V7(b9) – i|: In jazz, you will most typically find that although the V9 chord is acceptable when resolving to major, the ninth is always lowered (b9) when resolving to a minor chord. Like the major ii-V construct, however, you will need to listen closely for the numerous other acceptable alterations that can be used.

Other Common Functions of Dominants

After the ii-V7 dominant there are a number of uses of the dominant chord that recur in hundreds of standard jazz tunes, including the Blues Root, Tri-Tone Sub, Dominant II, and Dominant b7.

Let’s dig in:

- I7: Blues Root |I7 – IV7|: If you’ve made it this far in the post, you already know the dominant chord is used over the tonic to get that bluesy sound. Often the 13th or +9 forms of the chord are used for a little bit of twang, but I’ll get more into this in the next post.

- bII7: Tri-Tone Sub |bii7 – I|: This really belongs in the section above on 2-5’s, but it’s common to substitute the V7 with the dominant chord a tritone away. Note: don’t alter this any further.

- II7 (#11): Dominant 2 |I7#11 – iim7|: Lots of tunes sit on the dominant II7 to set up the ii of a ii-V. Whenever you see this (i.e. a D7 in the key of C), it’s conventional to ad a #11 to the chord.

- bVII7: Dominant b7 IV|: After moving from I to IV, the harmony will commonly move up another fourth to the flat-seven.

Cherokee one of the countless examples of tunes that follow conventional jazz harmony, utilizing a plethora of ii-V-I’s in addition to both the Dominant 2 and Dominant b7.

What’s Next?

Great, thanks for the theory lesson. But what’s the point?!?

Well, now it’s time to get to work. You need to train your ear, your brain, and your fingers. In my next post, I’ll continue following this slightly academic approach and map out the various forms of dominants, their alterations, and what you can (and CAN’T) play over them. We’ll also talk about how to practice harmony and get you on the road to becoming an honest harmonic sensei.

Well, now it’s time to get to work. You need to train your ear, your brain, and your fingers. In my next post, I’ll continue following this slightly academic approach and map out the various forms of dominants, their alterations, and what you can (and CAN’T) play over them. We’ll also talk about how to practice harmony and get you on the road to becoming an honest harmonic sensei.